NIDSコメンタリー 第331号 2024年6月21日 China’s Southwest Island Patrols: Freedom of Movement Through Encroachment

- Andrew Orchard, Mansfield Fellow at NIDS

Introduction

Two operational concepts, Near Seas Defense and Far Seas Protection, underscore the People's Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) current strategy.1

Near Sea Defense (近海防御) is the PLAN traditional mission, focused on defending territorial sovereignty and maritime interests. Missions in Near Seas emphasize naval operations within the first island chain to deter potential threats to China.2

The concept of Far Seas Protection (远海防卫) can be traced back to President Hu Jintao's 2004 introduction of the “New Historic Mission.” It is pivotal in the PLAN transformation. PLAN Missions have not solely focused on protecting Chinese worldwide interests. Far Seas Protection has reshaped the PLAN into a global navy, operating along distant sea lines of communications (SLOCs) that are vital now or in the future to the Chinese economy.3

Recognizing the implications, since 2010 the PLAN continues to diversify transit routes through the Southwest Islands. These operations normalize PLAN navigation through various straits and provides training value, while reducing reliance on a single access point.4

Southwest Islands and waterways map modified by author from Wikipedia.5

Southwest Island Patrol

Consistent with the PLA's 2020 Science of Military Strategy, maintaining a presence in important straits creates the favorable conditions for strategic operations.6 Accordingly, ETN has stepped up its presence along the Southwest Islands' transit routes.

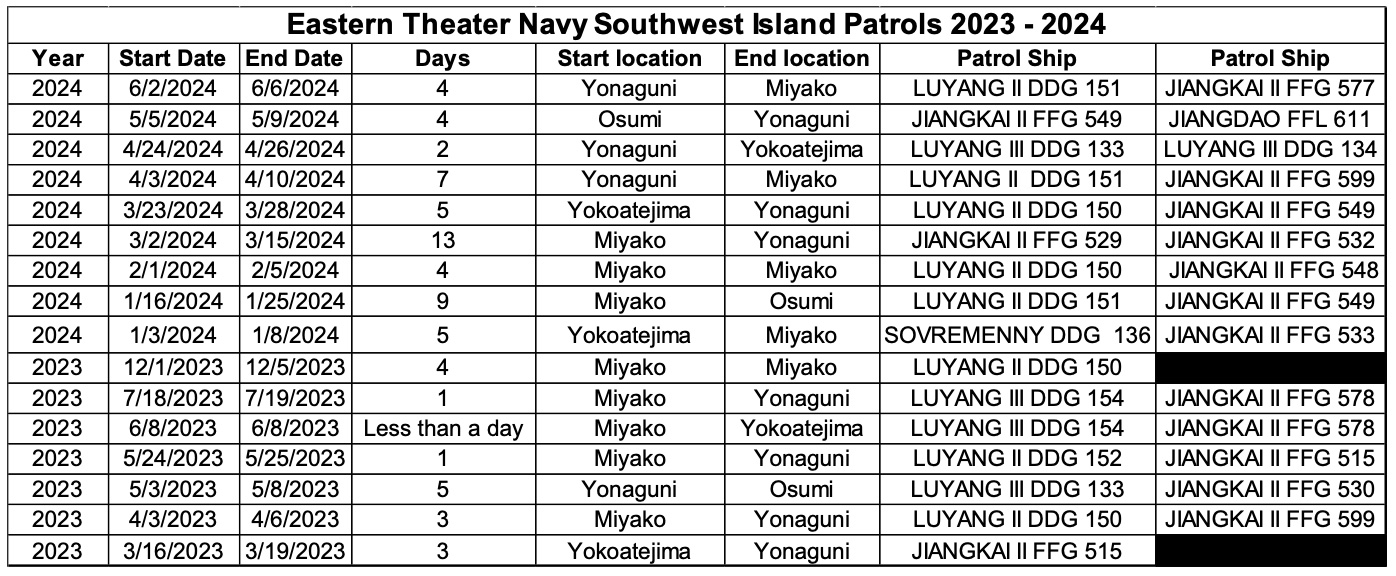

Over the past 15 months, ETN has conducted 16 multi-day Philippine Sea patrols near the Southwest Islands.7

ETN Southwest Island Patrols8

ETN combatants initially conducted the patrol monthly from March to July 2023 before reassuming the mission in December 2023. The initial six-month period was possibly a trial phase to evaluate the patrol.

Since December 2023, ETN combatants have conducted the patrol monthly.

All but two of the patrols included two combatants. A LUYANG II (TYPE 052C) DDG and JIANGKAI II (TYPE 054A) FFG comprised half of these patrols. Frequently utilizing LUYANG II DDGs helps explain why the ETN Sixth Destroyer Flotilla conducted most (75 percent) of the patrols, as all ETN LUYANG II DDGs are assigned to the flotilla.

ETN occasionally dispatched other combinations of combatants, including two LUYANG III (TYPE 052D) DDG in April 2024 and a JIANGKAI II FFG with a JIANGDAO (TYPE 056A) FFL in May 2024. Third Destroyer Flotilla has conducted three patrols since the mission's reassumption in December 2023.

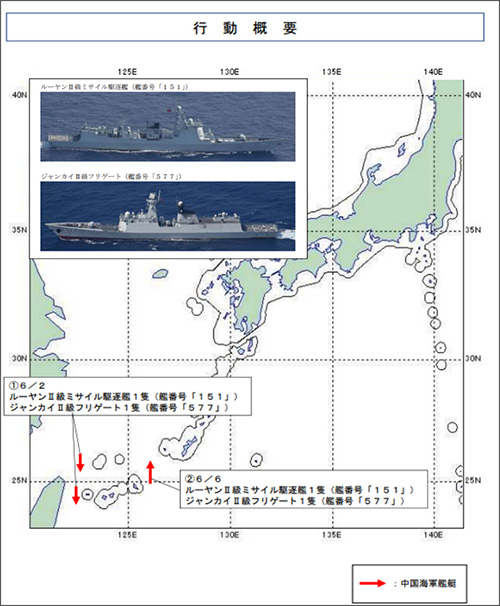

Japan Joint Staff press release graphic for the 2-6 June 2024 Southwest Island patrol.9

The average patrol is just four days (4.38) and tends to occur within the first ten days of a month (63 percent of the time). Half of the patrols departed the first island chain through the Miyako Strait, and almost all returned through another way, such as the Yonaguni Gap. Conversely, almost half (43 percent) of all patrols returned via the Yonaguni Gap after exiting the first island chain elsewhere. Equally notable, almost a third of the patrols have transited the unnamed strait between Amami Oshima and Yokoatejima, utilizing a narrow gap in Japanese territorial waters at the strait to exit the first island chain.10 The gap in territorial waters is important as international law allows other nations' submarines to travel submerged through the strait since the waters are in the Japanese contiguous zone.11 This route could potentially facilitate future submarine movements, a prospect underscored by (presumed Chinese) submarine submerged transit through these waters in June 2020 and September 2021.12

Silkworm Eating Strategy

By employing a gradual encroachment strategy (“Silkworm Eating” [蚕食]), the PLAN is normalizing its presence in and around the Southwest Islands, ensuring its freedom of movement beyond the first island chain.

The Chinese equivalent to the Western notion of "salami-slicing" tactics is the phrase "silkworm eating" (蚕食).13 The phrase in Chinese and Japanese means to encroach, making inroads slowly.14 This concept traces its origin to the chengyu(成語)to nibble away like a silkworm or swallow like a whale (蚕食鯨吞), meaning: "One can seize another's territory by gradual encroachment or wholesale annexation." The concept of gradual encroachment traces its origins to the State of Qin's consolidation tactics during the Warring States period in ancient China. The essence is gaining success by slowly making inroads, by nibbling away at something.15

The silkworm eating strategy has significant implications for regional security. China employs the strategy throughout the first island chain - from the almost daily PLA incursions into the Taiwan Air Defense Identification Zone (TADIZ) to the PLAN and China Coast Guard (CCG) patrols near Beijing maritime claims. The strategy's application recurrently normalizes Chinese operations, forcing other Asian nations to expend finite military-security resources (aircraft and ship readiness) in response. Beijing's actions likely seek to demonstrate capabilities, enforce China's claimed sovereignty (i.e. Scarborough Reef), and challenge other nations' legitimacy (i.e. TADIZ).16

As part of the 'silkworm eating' strategy, ETN deploys eight combatants daily for patrols near Japan and Taiwan (three and five, respectively). These patrols involve various activities, including surveillance, deterrence, and enforcement of China's maritime claims. The mission requires 13 percent of the ETN's corvettes, frigates, and destroyers to be underway each day. Establishing regular patrols over the past several years, including the recent addition of a Southwest Islands patrol, is likely a strategic move to alter the status of quo and enforce China's claims.17

Southwest Island Patrol and Taiwan Blockade

Altering the status quo in and around the first island chain enables Beijing to support its political objectives through military operations other than conflict.

The recent PLA response exercise (Joint Sword 2024A) to Taiwan President Lai's inauguration demonstrated the potential isolation of Taiwan. In close coordination with the CCG, PLA forces conducted training around Taiwan and its offshore islands, simulating a blockade during Joint Sword 2024A. As assessed by military expert Zhang Chi, this exercise is a reminder of the PLA's operational ability, showcasing their capacity to sever Taipei's energy imports and prevent U.S. aid during a contingency, making Taiwan "a dead island."18

While power warfare is the crux of achieving a blockade, maneuver warfare is vital in enabling the maritime superiority necessary for such operations. ETN demonstrated their prowess in effective and rapid operational maneuver at sea, strategically positioning forces along critical Taiwan SLOCs during Joint Sword 2024A. Freedom of movement through waters adjacent to Taiwan allowed ETN to gain decisive positions and conduct the exercise.

Gaining the necessary decisive position for the blockade of Taiwan is far more difficult for the ETN without freedom of movement through the Southwest Islands. Accessing eastern Taiwan SLOC only via Luzon Strait reduces ETN speed and agility as the ponderance of force must transit further to arrive on-station. Transiting to the east coast of Taiwan from the Sixth Destroyer Flotilla's homeport on Zhoushan Island via the Yonaguni Gap is much faster than going through the Taiwan Strait and the Bashi Channel. Reduced transit routes also simplifies scouting operations against the ETN, increasing the risk to the force. The additional risk likely makes setting conditions for a blockade harder for the ETN to obtain as such operations are considered low risk given established maritime superiority.

Conclusion

Patrolling the Southwest Islands and maintaining freedom of movement through these waterways is crucial to Beijing. It enables both a maneuver (“movement to attack” – tactical level of war) and mobility (“movement to the scene of battle” – operational or strategic level of war) advantage, as demonstrated by the above Taiwan blockade scenario.19

From a tactical perspective, the Southwest Islands offer a wealth of advantages. Their proximity and numerous transit routes not only foster tactical agility but also enable patrolling forces to swiftly secure a favorable position along the Taiwan SLOCs. Moreover, the ability to complicate scouting through disaggregated movement via multiple waterways to favorable positions underscores the value of maintaining access through the Southwest Islands.20

The Southwest Islands' waterways could be a key component of ETN's strategy. Their proximity to ETN bases offers a faster route than the Luzon Strait, enhancing mobility capacity. Enhanced mobility potentially aids in establishing favorable conditions for complex maritime operations, such as blockades or amphibious assaults. Additionally, the ETN could utilize these waterways, like the unnamed strait between Amami Oshima and Yokoatejima, to position submarines along advisory SLOCs during a Taiwan contingency.21 By leveraging this capacity, the ETN could efficiently move forces and execute plans.22

Maintaining these advantages likely requires further Southwest Islands patrols over the next several years. Even if they are still short in duration, these patrols only enhance the ETN's ability to concentrate force and take advantage of a situation expeditiously. The arrival of additional surface forces to the ETN may result in additional presence and a nibbling away at the status quo.

Acknowledgement:

The author would like to thank NIDS for the award of a NIDS Fellowship (May-June 2024), during which time this Commentary was completed

Profile

- Andrew Orchard is a U.S. Navy officer and current Mansfield Fellow.